October, 2000

The Other Michelangelo

| By Joseph Phelan |

Michelangelo Merisi (1571-1610), called Caravaggio, is the second Michelangelo, born a few years after the death of Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), sculptor of the Pietà and painter of the Sistine Chapel.

1. The Exhaustion of the High Renaissance and the Rise of Mannerism

1. The Exhaustion of the High Renaissance and the Rise of MannerismPrior to Caravaggio's arrival on the Roman scene in the last years of the 16th century, Italian Renaissance painting appeared to be exhausted. The High Renaissance achievements of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael, based as they were on intense competition among gigantic egos and stupendous talents, reached such a peak that further serious art seemed impossible.

How could a young artist aspire to equal or surpass such works as the Mona Lisa, the Last Supper, the Sistine Chapel and Raphael's Stanzes - still the most popular paintings in the world? The Venetian achievement of Giorgione, Titian and Tintoretto also seemed played out. The deaths of Michelangelo and Titian signaled the end of the High Renaissance.

Moreover,in their last works Leonardo, Michelangelo and Titian all seemed to question the very foundations of their own achievement as well as the goodness of this world. Each artist spent his last years working in an apocalyptic mode. Leonardo's many drawings of a Watery Deluge which destroys the world, Michelangelo's Last Judgment and Titian's Crowning with Thorns and his last Pietà are works of extraordinary doubt, despair, and disillusionment.

In reaction, younger painters either tried to outdo the late works or moved into areas of fantasy avoided by the High Renaissance, breaking rules of decorum, of subject matter, and of unity (see Mannerism). Caravaggio turned this situation around. He put European painting back on track returning the focus to what we all perceive and what we all know. But he did it with a twist.

Caravaggio was destined to electrify painting in the early years of the 17th century, causing shockwaves which would be felt throughout most of Europe as each generation of painters caught on to his revolution in easel painting. The Carravaggists (early followers in Italy, Netherlands, Flanders and Spain) were followed by the generation of giants, Rubens, Rembrandt, Vermeer and Velázquez, each borrowing from the man who painted with a striking directness that compels the spectator to participate in the action.

2. The New Realism

2. The New RealismCaravaggio's revolution consists in two innovations. As a painter of mostly devotional art, he necessarily focused on figures and events from the New Testament but he took more seriously than any painter since Masaccio the mundane yet monumental quality of Christianity.

The typical Caravaggio religious painting increased the mundane quality of the events by using Roman street people as the model for the Apostles and Mary. But he also increased the monumentality of the paintings by larger than life proportions, highly theatrical lighting and by crowding his significant figures into an extremely shallow space thus capturing the attention of the spectator with dramatic and immediate effects.

Some of Caravaggio's canvases were at first rejected by the Church as being inappropriate (it was said that he used the body of a dead prostitute fished out of the Tiber as his Mary in the Death of the Virgin), but he had a highly sophisticated audience.

3. In Your Face

3. In Your FaceYet Caravaggio's heightened realism eventually won over the his patrons because realism made a certain kind of sense to the Post Reformation Church which was interested in using art to bring the people back to the Church.

The religion whose savior is born in the humblest circumstances, who during his three year pubic ministry consorted mainly with lowlifes, criminals, publicans and the possessed and whose harrowing death on the cross was, in the words of St. Paul, a Stumbling block to the Jews and Foolishness to the Greeks (Corinthians I, 23), is a religion which ought to shock the genteel assumptions of each generation of its followers. Caravaggio was the first great religious painter to understand this paradox.

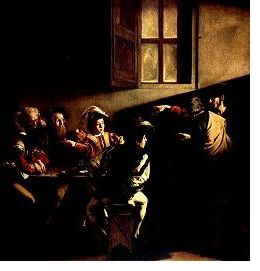

His formula is a shallow space crowed with a few significant figures and maximum concentration on them. He aimed at the maximum emotional sympathy of the viewer inviting him to enter the painting or making the painting seem to push out of the canvas (See the first Supper at Emmaus, illustrated at the top of the page). He is the master of dramatic theatrical lighting spotlighting the main figures faces while their bodies and those around them are in shadows (See The Calling of Matthew, shown above left).

4. The Return to the Tradition

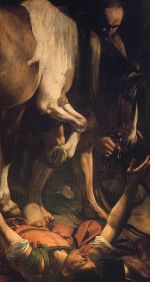

4. The Return to the TraditionCaravaggio's greatest achievement, however, is to have revived the best of the monumental tradition of the first Michelangelo. To begin with he dared to contest with the Master in the arena where Michelangelo had no rivals, the terrible vision of the last paintings.

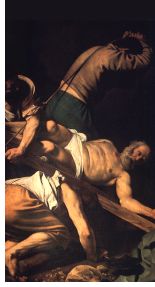

Michelangelo Buonarroti's The Conversion of St. Paul (Saul) and The Crucifixion of St. Peter are works that were much too terrible for their century and for any century but our own (they are still off limits to visitors to the Vatican). Caravaggio's versions, illustrated here, show how seriously he took the lesson of the Master. Conversion and Crucifixion are the beginning and end of Michelangelo's teaching both about life and art. Caravaggio clarified, corrected and advanced that tradition in his work.

Caravaggism on the Web

- Web Gallery of Art, as usual with Italian Renaissance artists, does yeoman service here with many of Caravaggio's paintings organized chronologically. In addition, they have a mini-tour of Caravaggism,which sketches his influence on artists in several European countries.

- The National Gallery of Art still has its Saints and Sinners exhibit on line buried under past exhibits A high definition image of the breaktaking the Taking of Christ is the central item here.

- The North Carolina Museum of Art has archived their good exhibit of Caravaggio and his Northern followers.

- The Detroit Institute for Art has a Caravaggio and His Influence feature as part of its permanent collection.

- The National Gallery of Canada's Cybermuse site has interesting work by several of his followers including Orazio Gentileschi's Lot and his Daughters and Rubens' homage to Caravaggio, The Entombment. Also Poussin's only bow to Caravaggio at the beginning of his career, the Martyrdom of St. Erasmus.

- The New York Times Book Section has archived a special feature on Peter Robb, the author of M: The Man Who Became Caravaggio. It includes some good slides of the paintings and an interview in RealAudio format.

- For the more adventurous, World Art Treasures offers The Night Prince - a variety of approaches to Cavaraggio.

This article is copyright 2000 by Joseph Phelan. Please do not republish any portion of this article without written permission.

Joseph Phelan can be contacted at joe.phelan@verizon.net