Feature Archive |

Notorious Portraits

| By John Malyon |

| Overflattering Portraits I: Napoleon | |

| Overflattering Portraits II: Van Dyck and Holbein | |

| | Grotesques and Horrors |

| Illness and Deformity | |

| Madmen | |

| Read the first part of this article from last month |

Grotesques

The word grotesque literally means grotto-like. Roman grottoes were decorated with fanciful monsters of various kinds, and some Renaissance artists began to experiment with the same kind of motif. The term refers more generally to a genuinely or distortedly hideous figure, drawn for decorative effect or for the artist's amusement rather than to create genuine horror.

One of the truly great grotesques is the almost simian portrait by Quentin Metsys of A Grotesque Old Woman. Her face is hideous, but the low-cut dress she's wearing is downright scarifying. Little is known with certainty about this artist, but he is also widely known as Quinten Metsys, Quentin Massys, Quentin Metzys and Quentin Messys, so we can assume he suffered from a handwriting disorder of some kind.

Metsys based his old woman on a drawing (at left) by Leonardo da Vinci, who got enormous pleasure from studying the nature of the human face (as well as everything else under the Sun).

Another famous image is Domenico Ghirlandaio's portrait of an Old Man with a Child. It's a wonderfully sympathetic image of a loving grandfather who happens to have a nose like a cauliflower.

Less sympathetic is Marinus van Reymerswaele's portrait of Two Tax Gatherers. The older man(?) is severe (although the seriousness is somewhat undercut by the bizarre headpiece), while the younger man leers at the viewer with a grasping, uncomprehending leer. Popular demand encouraged Reymerswaele to paint many versions of this scene, so it's possible tax collectors were not as popular in the 16th century as they are today.

In more modern times, the photographer Weegee (Arthur Fellig) prowled the streets of New York City, documenting the most sensational murders, arrests and late-night spectacles he could find. One of his more bizarre portraits is a kind of inside-out photograph of Marilyn Monroe.

Finally, anything by Ralph Steadman, the longtime illustrator for the "gonzo" writings of Hunter S. Thompson, is as grotesque as it gets.

Horrors

Much darker and more terrifying are the horrors, cruelties perpretrated on mankind.

Many artists have mined their deepest fears and phobias for imagery capable of representing the horrors of Hell. But far more moving are the eyewitness images of the horrors visited by mankind upon itself: never-ending war and ceaseless martyrdoms, inquisitions and witch-burnings in the name of Religion.

Hieronymus Bosch's paintings The Garden of Earthly Delights and The Temptation of Saint Anthony are probably the most famous tableaux of the legions of Hell.

The Last Judgment of Michelangelo and The Gates of Hell of Auguste Rodin are two other ambitious representations of Hell and damnation which are so densely packed with detail that it's hard to do justice to them online.

At the root of the Christian religion is the martyrdom of the Passion of Christ. Many Christian saints also died horrible deaths which were enthusiastically documented by Renaissance artists. Martyrs include Saint Apollonia (had her teeth pulled out by force and was burned alive - she is now the patron saint of toothache sufferers), Saint Florian (drowned), Saint Barbara (beheaded), Saint Catherine of Alexandria (was to be broken on the wheel until it was miraculously destroyed, so she was beheaded instead), the Ten Thousand at Nicomedia (put to the sword), and so on.

At the root of the Christian religion is the martyrdom of the Passion of Christ. Many Christian saints also died horrible deaths which were enthusiastically documented by Renaissance artists. Martyrs include Saint Apollonia (had her teeth pulled out by force and was burned alive - she is now the patron saint of toothache sufferers), Saint Florian (drowned), Saint Barbara (beheaded), Saint Catherine of Alexandria (was to be broken on the wheel until it was miraculously destroyed, so she was beheaded instead), the Ten Thousand at Nicomedia (put to the sword), and so on.(For many more paintings of saints meeting bad endings, try doing a title search on "martyrdom".)

In many of these works, the horror is somewhat muted because the martyrs face death with a beatific calm. Bergognone's Saint Peter the Martyr (above) looks a little gray but doesn't seem to be suffering much under the circumstances. And Michelangelo's Saint Peter (left) frankly looks a little pissed off at being crucified. Not so with the morbid paintings of Spanish painter Jusepe de Ribera, however. His saints are elderly and haggard (see Saint Onuphrius for example) and they suffer very real physiological effects of torture (as in The Martyrdom of Saint Andrew), as if Jusepe had seen a few torture sessions in his day.

In many of these works, the horror is somewhat muted because the martyrs face death with a beatific calm. Bergognone's Saint Peter the Martyr (above) looks a little gray but doesn't seem to be suffering much under the circumstances. And Michelangelo's Saint Peter (left) frankly looks a little pissed off at being crucified. Not so with the morbid paintings of Spanish painter Jusepe de Ribera, however. His saints are elderly and haggard (see Saint Onuphrius for example) and they suffer very real physiological effects of torture (as in The Martyrdom of Saint Andrew), as if Jusepe had seen a few torture sessions in his day.Jusepe's specialty was the portrayal of men being flayed alive. He is best known for his many paintings of the Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, who suffers this fate. Jusepe's other treatments of this scene can be found in Washington's National Gallery of Art, the Prado, and the University of Michigan Museum of Art. He also tackled The Flaying of Marsyas several times, and versions can be seen in the Musee Royaux des Beaux Arts in Brussels and the Museo Nazionale di San Martino in Naples.

|

Another Spanish artist especially well suited by mood and by circumstance to portray the horrors of war was Francisco de Goya. He had an especially bleak artistic vision, and his Black Paintings are among the darkest images ever painted. Disasters of War is a series of 85 engravings, produced by Goya after witnessing the brutal Peninsular War between France and Spain. The images are rarely heroic, focusing instead on the nightmarish atrocities which became commonplace. The University of Adelaide has a Study Guide to War Art which shows about two-thirds of the engravings. |

|

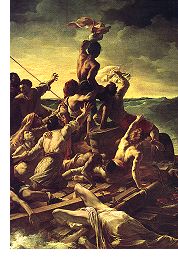

Finally, Théodore Géricault created a minor sensation with his Raft of the Medusa. While not so much a portrait of individuals, it is a graphic recreation of a particularly black incident at sea. The darkly-named Medusa was a naval frigate which hit a reef and sank en route to Senegal. Its officers were packed into lifeboats, while the rest of the crew were towed behind, on a raft. In due course the boats cut the raft loose and left 150 men to perish.

Finally, Théodore Géricault created a minor sensation with his Raft of the Medusa. While not so much a portrait of individuals, it is a graphic recreation of a particularly black incident at sea. The darkly-named Medusa was a naval frigate which hit a reef and sank en route to Senegal. Its officers were packed into lifeboats, while the rest of the crew were towed behind, on a raft. In due course the boats cut the raft loose and left 150 men to perish.After 12 days, the few who remained alive on the raft were picked up by another ship, returning to France with blood-curdling stories of the abandonment and subsequent incidents of murder and cannibalism.

Géricault sensed the opportunity to create a great work, and threw himself into the project. He studied corpses in the morgue, interviewed the survivors of the shipwreck, built a scale model of the raft in his studio, and even shaved his head so as not to be tempted to waste time at his usual night haunts. Even his studies for the canvas are magnificent; they include this gouache study and this oil sketch.

Géricault's painting inflamed what was already a major embarrassment to the French government. It came out that the captain was a political appointee who was incompetent, overriding the navigational advice of his crew and hitting a reef in broad daylight. And not only was the cutting loose of the raft an act of inhuman cowardice, it was later learned that the Medusa had never broken up and there had been no immediate need to leave the ship at all.

| Continue to next page: Illness and Deformity |

This article is copyright 2000 by John Malyon. Please do not republish any portion of this article without written permission.

John Malyon can be contacted at jmalyon@artcyclopedia.com