Feature Archive |

Notorious Portraits

| By John Malyon |

| Overflattering Portraits I: Napoleon | |

| Overflattering Portraits II: Van Dyck and Holbein | |

| Grotesques and Horrors | |

| | Illness and Deformity |

| Madmen | |

| Read the first part of this article from last month |

Illness

In 1346, an armed conflict broke out between Tartars and Genoese traders in the city of Caffa, in Crimea on the Black Sea. Plague had broken out in the area, and as the Tartars lay siege to the city they placed the corpses of plague victims on catapults and launched them over the city walls.

The Genoese began to die off from the plague and retreated back to Genoa, taking the disease with them. This, according to legend, is how the Black Death came to Europe.

Between 1347 and 1352, it was as if the end of the world had arrived. Twenty-five million - one person in three - are thought to have died in this first outbreak or the plague. Siena is known to have lost 60% of its population. There were recurring outbreaks on a smaller scale for centuries.

Between 1347 and 1352, it was as if the end of the world had arrived. Twenty-five million - one person in three - are thought to have died in this first outbreak or the plague. Siena is known to have lost 60% of its population. There were recurring outbreaks on a smaller scale for centuries.In fact, many historians consider the creative outpouring of the Renaissance to be a more or less direct result of the massive economic, social and psychological upheavals caused by the Black Death. The argument is too complex to go into here, but I can explain it by analogy: When Gary Busey totalled his Harley-Davidson and nearly died, afterward he was able to replace it with a much faster bike. Same principle at work.

Strangely, there doesn't seem to be much direct chronicling of the Black Death in art of that time (Gros documented Napoleon's famous visit to the pesthouse at Jaffa, but that was almost 500 years later). Despite the seeming newsworthiness of the coming of the plague, painting and sculpture were dedicated almost exclusively to distant religious subjects until well into the next century. Manuscript illustrations (such as the example at right), while in most cases not as polished as paintings of the era, are a better source of pictures of daily life.

One indirect effect of the plague was the rise in popularity of Saint Sebastian. He had been tied to a tree by Diocletian's soldiers and shot with arrows - he miraculously survived, but is traditionally represented as pierced with many arrows. He became a patron saint of plague victims, presumably because one of the main symptoms of the disease is the presence of stabbing pains in the body.

One indirect effect of the plague was the rise in popularity of Saint Sebastian. He had been tied to a tree by Diocletian's soldiers and shot with arrows - he miraculously survived, but is traditionally represented as pierced with many arrows. He became a patron saint of plague victims, presumably because one of the main symptoms of the disease is the presence of stabbing pains in the body.One important image tying Sebastian to the Black Death, dating from 150 years after the first outbreak, is Josse Lieferinxe's panel, Saint Sebastian Interceding for the Plague Stricken.

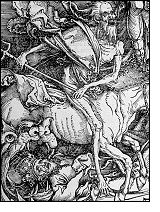

A second effect of the plague was the frequent use of extremely morbid imagery. Death was ever-present and could strike down anyone with little forewarning. Death incarnate makes many appearances in paintings of the period, and apocalyptic images like Pieter Bruegel's 1562 nightmare The Triumph of Death and Albrecht Dürer's Four Horsemen of the Apocalpyse were common.

Syphilis is another disease which devastated Europe, as I have already mentioned briefly in the context of Henry VIII. Manet, Gauguin and many, many other famous men are thought to have suffered from it.

Its effects can be seen in the stunning portrait, Las Meninas (The Maids of Honour), by Diego Velázquez. The dwarf on the right-hand side of the scene exhibits a low nasal bridge, known as a "saddle nose". This is a symptom of congenital syphilis.

Bronzino's famous painting, An Allegory with Venus and Cupid, is also thought to show the effects of syphilis in symbolic form (the screaming man in the background). As with many allegorical paintings, the meaning is a little opaque, especially to a modern viewer. The National Gallery of London declines to offer an interpretation, stating that "agreement... on the meaning of the picture has not been reached.".

Let's get out of this section on a upbeat note: Cluck Close is known for his huge, meticulously precise paintings of the human face. One such portrait, of his father-in-law Nat Rose, was lent to New York City's Whitney Museum, where it happened to be admired by an ophthalmologist.

The doctor recognized the early signs of a carcinoma in one eye, and Rose was advised to get a check-up. The cancer shown by Close's astoundingly accurate portrait was confirmed and was removed. Thus Nat Rose's eyesight, and possibly his life, were saved by a work of art.

There's a profound message in there somewhere.

Deformity

In times past, which were not so different from today, people had a macabre appetite for so-called "freaks" of various kinds. People paid to see giants, hermaphrodites and half-men-half-fish at carnivals, and kings kept dwarves in their courts for amusement. Not only did these poor souls lead miserable lives, but in the absence of any significant knowledge of genetics or of human physiology, they seemed to be suffering a personal punishment from God.

In times past, which were not so different from today, people had a macabre appetite for so-called "freaks" of various kinds. People paid to see giants, hermaphrodites and half-men-half-fish at carnivals, and kings kept dwarves in their courts for amusement. Not only did these poor souls lead miserable lives, but in the absence of any significant knowledge of genetics or of human physiology, they seemed to be suffering a personal punishment from God.Several quite respectful and affectionate portraits of court dwarves were made by great painters. Anthonis Mor painted Cardinal de Grandvelle's Dwarf. Jan van Eyck painted the nobleman Baudouin de Lannoy, who looks to my eyes to be a dwarf. And it must have been hard to get a basketball game together at the Spanish court: half the people in Diego Velázquez' paintings are under three feet tall. In addition to the dwarf in the great Las Meninas, mentioned above, he painted Francisco Lezcano, Don Antonio el Inglés, Don Juan Calabazas, Sebastian de Morra and Prince Balthasar Carlos with a Dwarf.

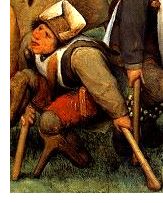

This discussion wouldn't be complete without a return to our master of horrors, Jusepe de Ribera. He created several startling images which are notable for their humane treatment of the subjects. The portrait of the young beggar now known as the Clubfooted Boy would have been used by most artists as a device to drag out feelings of horror or of pity. But Jusepe shows him smiling, in a grand and confident mood. This trick allows the viewer to see the boy as a real human being rather than as a caricature, and evokes a much more genuine set of emotions.

A far more shocking portrait is Bearded Woman Breastfeeding. The woman is shown along with her husband and her child, with a breast out for her child to take. The couple are specifically named in the painting as Felix and Magdalena Ventura. Although there are some disturbing elements (such as the exposed breast, which seems oddly placed and may or may not have hair on it), the scene is handled neutrally, with some solemnity.

The Catholic Encyclopedia says in reference to these paintings that Jusepe takes "a gloomy pleasure in humiliating human nature," but I think that is far from the truth. These are honest portrayals of real people, and there's no humiliation in that.

| Continue to next page: Madmen |

This article is copyright 2000 by John Malyon. Please do not republish any portion of this article without written permission.

John Malyon can be contacted at jmalyon@artcyclopedia.com