|

| |

Feature Archive

Cézanne in Provence: From Misanthrope to Modernist

Cézanne in Provence

At the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., through May 7, 2006

Moving to Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence, France, June 9–Sept. 17, 2006

By Joseph Phelan By Joseph Phelan

|

|

|

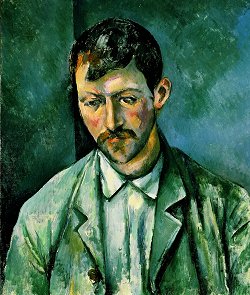

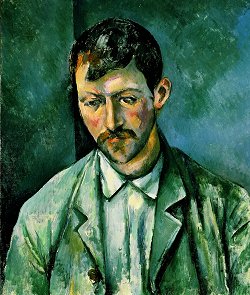

Peasant (Le paysan)

Paul Cézanne was of the same generation as Monet, Degas and Renoir, even exhibiting his works with them in the early years of the Impressionist movement and painting side-by-side with the likes of Camille Pissarro, yet he really stands apart from the Impressionists for a number of reasons.

While the Impressionists were aspiring to follow Baudelaire's admonition to become the painters of modern urban life by chronicling the denizens of Paris at work and play, Cézanne soon turned his back on the city and its inhabitants and returned to his family home in Provence. Always something of a loner, perhaps even a misanthrope in the classic French sense, Cézanne spent the rest of his life working in the solitude of his home region engaging in a silent dialogue with its valleys, seaports, stone quarries and mountain peaks.

So it is appropriate in this centennial year of his death that the National Gallery in Washington - the home to one of the greatest collections of Cézanne's work -- in collaboration with the Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence -- has brought together over one hundred oil paintings and watercolors by this great modern artist. In a monumental gesture, the due homage is finally being paid to the true native son of Aix-en-Provence. The result is the most intimate portrait thus far of the places where the Master of Aix lived and worked over a period of forty five years.

So intense was Cézanne's engagement with his native countryside that it marks him, in the words of the senior curator of French painting at the National Gallery, Philip Conisbee, as the last of the great landscape painters of the French tradition. That Cézanne saw himself in this way is indicated by his remark that There are treasures to be taken away from this country, which has not yet found an interpreter worthy of the riches it offers.

"There are treasures to be taken away from this country, which

has not yet found an interpreter worthy of the riches it offers"

|

The crude bluster and rustic manner which Cézanne affected in his early personal demeanor was reflected in a painterly style adopted in earnest imitation of the realism of Gustave Courbet. Here we notice the dark palette of heavily impastoed paint applied vigorously roughly to the canvas. Strong works such as these such however are not enough to earn an artist a place in the history of 19th century art, much less assume the title of the father of modern painting. But Cézanne eventually put this technique to such striking use that it represented a new approach to the discipline of painting itself. In one of the most powerful works in the exhibit we see a larger than life image of Cézanne's very conservative father seated in his chair reading a socialist newspaper. We immediately gain the impression that this towering figure is almost built out of paint.

Cézanne's Impressionist mentor Camille Pissarro introduced him to plein air painting and a lighter palette. This enabled the younger man to capture his beloved family estate Jas de Bouffan (House of the Wind) and its surrounding landscape in the dappled sunlight. Cézanne's loose brushy strokes suggest nothing so much as the wind moving through the trees eloquently capturing a sense of dynamics on the flat picture plane. We see that early on he had an eye for the solidity of forms which he finds both in the great cube of the house as well in the abstract shapes made by the bare branches of the chestnut trees in winter.

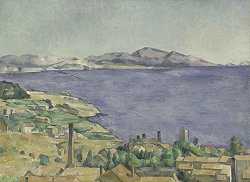

Washington and Paris share similar (bad) winter weather. So it is especially invigorating to step from the middle of this season into the glorious sunlight of a Provence summer. As we do so, we hear the voice of Cézanne writing to his friend Pissarro about the frisson which he experienced on returning from Paris to see the view of the Mediterranean from the port of Estaque: The sun here is so terrific that objects appear silhouetted not only in white or black, but in blue, red, and brown, violet. I may be wrong but it seems to me this is the opposite of modeling.

From a basis in such "sensations," Cézanne was able to explore how color and light defined form in the mind's eye and this in turn led to his seminal innovations in the structure and composition of painting.

While the Impressionists painted quickly, seeking to capture the most ephemeral qualities of light, Cézanne began with his "sensations" and then composed slowly, almost architecturally, sometimes taking years to finish his canvases. His distinguishing objective is best summed up in his famous remark that his ambition was "to make of impressionism something solid and enduring, like the art of the museums".

Here a contrast with an Impressionist rival, Monet, is appropriate. When Cézanne characterized Monet as "just an eye, but what an eye", he was asserting the importance of the cerebral in his own art. The exhibit illustrates how the artist used Provence as a kind of analytical laboratory; his hometown became a kind of laboratory where he could study the atmospheric quality of his surroundings in depth. Here he could portray the same subjects be they mountains, seacoast, quarries, or indoor subjects like still lives and card players, with infinite care over numerous repetitions of distillation. Each time through he would analytically dissect his subject and then build it up anew as a towering shimmering composition designed to make the underlying structure of the subject shine forth.

Cézanne did not really expect many of his paintings to please

or even to fully make sense to many contemporary viewers

|

Although it is not emphasized by the exhibit, the fact is that Cézanne did not really expect many of his paintings to please or even to fully make sense to many contemporary viewers. He was in fact frequently ignored or ridiculed throughout his career. Some of the paintings in the show seem unfinished even by the radical standards established by the Impressionists. Fortunately Cézanne did not need to sell paintings for a living because of the wealth bequeathed to him by his father. He was thus in a position to work for years on some of these pieces with no thought as to how or when they might be sold.

Only a few paintings in his whole oeuvre actually bear Cézanne's signature. Thus when his name does appear on a work it is a definite indication that the piece was complete by Cézanne's standards and that he was ready for it to be exhibited. We may infer from this practice that the non-signed works were in fact never deemed by him to have been finished. They thus provide a window into the process of artistic creation. As unfinished works they can only represent a stage on the way to some ultimate end envisioned by the artist but not yet attained. We might say of Cézanne that, like the old painter Frenhofer in Balzac's Unknown Masterpiece, his unfinished work is greater than the truly finished work of many other artists.

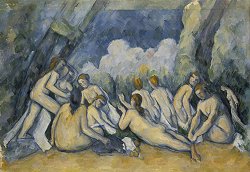

As one heads toward the last rooms of the exhibit, one cannot help but notice groups of striking male and female nude bathers. These were studies for a series of three large canvases devoted to a group of naked females sitting in a forest or park setting. Cézanne viewed these compositions as the culminating achievement of his art, works that would rival or equal those of Titian, Veronese and Rubens, which he had studied and adored in the Louvre.

The results here however were anything but a pleasure to human eyes. In fact they were considered so jaw-droppingly ugly in Cézanne's lifetime that they were never exhibited. Even his admirers among the critics and fellow painters were baffled by these works. Indeed The Great Bathers, loaned by the National Gallery in London, is a startling work by any standard. The nude women among the trees look more like trees and the trees look more feminine than the figures, creating an unsettling dialogue between the animate and the inanimate involving menacing faces, gross proportions and transcendental goddess like qualities. This was the "horrible, ugly" work which made Picasso and Matisse sit up and take notice of Cézanne. We can see in it the artistic roots of such masterpieces as Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and Matisse's Joy of Life.

The National Gallery of Art has an elaborate web feature for the show. Readers in the Washington D.C. area or visitors should check the programs and events section of the NGA website for information about introductory gallery talks and scholarly lectures. A new high definition television documentary will air on WETA TV 26 on March 2, 2006.

Also, a mini-site for last summer's Cézanne & Pissarro: Pioneering Modern Painting 1865-1885 at MOMA is still online.

Note: Nicole Ferdinando helped with the research for this article.

|

Past Articles

2006

Angels in America: Fra Angelico in New York, by Joseph Phelan

2005

Notes on New York (NoNY), by Joseph Phelan

The Greatest Painting in Britain

French Drawings and Their Passionate Collectors, by Joseph Phelan

Missing the Picture: Desperate Housewives Do Art History, by Joseph Phelan

The Salvador Dalí Show, by Joseph Phelan

2004

Boston Marathon, by Joseph Phelan

Philadelphia is for Art Lovers, by Joseph Phelan

Featured on the Web: Understanding Islamic Art and its Influence, by Joseph Phelan

Independence Day: Sanford R. Gifford and the Hudson River School, by Joseph Phelan

The "Look" of Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ, by Joseph Phelan

The Importance of Being Odd: Nerdrum's Challenge to Modernism, by Paul A. Cantor

2003

Advent Calendar 2003, narrated by Joseph Phelan

If Paintings Could Talk: Paul Johnson's Art: A New History, by Joseph Phelan

Mad Max [Max Beckmann], by Joseph Phelan

Marsden Hartley: The Return of the Native, by Joseph Phelan

Jean-Antoine Houdon: Sculptor of the Enlightenment, by Joseph Phelan

Frederic Remington's Nocturnes, by Joseph Phelan

Magnificenza! Titian and Michelangelo, Manet and Velazquez, by Joseph Phelan

Masterful Leonardo and Graphic Dürer, by Joseph Phelan

Favorite Online Art Museum Features, by Joseph Phelan

Studies for Masterpieces, by John Malyon

2002

Portrait of the Artist as a Serial Killer, by Joseph Phelan

Renoir's Travelling, Bonnard's "At Home", by Joseph Phelan

The Philosopher as Hero: Raphael's The School of Athens, by Joseph Phelan

The Greatest Works of Art of Western Civilization

Celebrating Heroes; Celebrating Benjamin West, by Joseph Phelan

Chasing the Red Deer into the American Sublime (Education and the Art Museum, Part II), by Joseph Phelan

Planning Your Summer Vacation, by Joseph Phelan

Education and the Art Museum, Part I, by Joseph Phelan

Unsung Griots of American Painting, by Joseph Phelan

The British Museum COMPASS Project, interview by Joseph Phelan

Robert Hughes, Time Magazine Art Critic: Biography and Writings

2001

Software review: Le Louvre: The Virtual Visit on DVD-ROM, by Joseph Phelan

Tragedy and Triumph at Arles: Van Gogh and Gauguin, by Joseph Phelan

Her Last Bow: Sister Wendy in America, by Joseph Phelan

Love, Death and Resurrection: The Paintings of Stanley Spencer, by Joseph Phelan

Who is Rodin's Thinker?, by Joseph Phelan

Celebrations North and South, by Joseph Phelan

Rubens and his Age, by Joseph Phelan

Great Reproductions of Great Paintings

The Passion of Christ, by Joseph Phelan

Edouard Manet: Public Spaces, Private Dreams, by Joseph Phelan

Henry Moore and the British Museum: The Great Conversation, by Joseph Phelan

2000

Notorious Portraits, Part II, by John Malyon

Notorious Portraits, Part I, by John Malyon

The Other Michelangelo, by Joseph Phelan

The Art of Drawing, by Joseph Phelan

Poussin and the Heroic Landscape, by Joseph Phelan

Great Art Museums Online, by Joseph Phelan

Venetian Painting and the Rise of Landscape, by Joseph Phelan

Forbidden Visions: Mythology in Art, by Joseph Phelan

Themes in Art: The Passion of Christ, by Joseph Phelan

Web site review: Christus Rex

Web site review: National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., by Joseph Phelan

Online exhibit review: Inuit Art: The World Around Me, by John Malyon

Poll: Who is Producing the Most Interesting Art Today? (Results)

Poll: Who is Producing the Most Interesting Art Today? (Part II)

1999

Poll: Who is Producing the Most Interesting Art Today? (Part I)

Spotlight on The Louvre Museum

Spotlight on Impressionism

Spotlight on Optical Art

Spotlight on Animals in Art

Spotlight on Surrealism

Spotlight on Sculpture

Spotlight on Women in the Arts

Spotlight on The Golden Age of Illustration

Spotlight on Vincent van Gogh

Spotlight on Great Art

|