|

Whatever you think of Dan Brown's Da Vinci Code and its movie version, the sheer audacity of his thesis of Leonardo as grand heretical artist devoted to the "sacred feminine" and constantly in conflict with the Catholic Church seems breathtaking. Yet this legend of Leonardo is only the latest version of a literary enterprise which began long ago with Giorgio Vasari, Leonardo's first biographer and has among its representatives Oscar Wilde's mentor, a Russian philosophical novelist and Sigmund Freud.

Whatever you think of Dan Brown's Da Vinci Code and its movie version, the sheer audacity of his thesis of Leonardo as grand heretical artist devoted to the "sacred feminine" and constantly in conflict with the Catholic Church seems breathtaking. Yet this legend of Leonardo is only the latest version of a literary enterprise which began long ago with Giorgio Vasari, Leonardo's first biographer and has among its representatives Oscar Wilde's mentor, a Russian philosophical novelist and Sigmund Freud.

Only three decades after the death of Leonardo, Giorgio Vasari published the first edition of an extraordinary work called The Lives of the Most Excellent Architects, Painters and Sculptors. Vasari single-handedly invented the discipline of art history and worked out an interpretation of it which is so persuasive that it has remained the dominant view today.

His book is an enormous collection of individual biographies of Italian artists, tracing the evolution of Renaissance art from the times of Cimabue and Giotto, when the art of painting was rediscovered, to Vasari's own day when Michelangelo brought it to the pinnacle of perfection with his murals on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Paul Barolsky of the University of Virginia thinks Vasari is "unarguably the single greatest writer about art in the entire history of literature".

While Vasari's biography preserves basic factual information about the artist that would otherwise have been lost, its central importance in Barolsky's eyes is to have "invented" the legend. For instance, Vasari tells us that Leonardo died in the arms of the King of France. Not true, according to historical records: the King was somewhere else that day. But what a picture!

Readers who pick up the Lives today will be surprised to see that side by side with the historical "facts", the book is studded with delightfully unhistorical fables. In fact, there is less art history than fiction in the book, so much so that Barolsky also calls Vasari "one of the greatest novelistic authors of the modern period"

We find in the pages of Vasari the germ of the notion that Leonardo was in conflict with the Church because of his scientific inquiries. In the first edition of Vasari's famous Lives of the Artists, he writes that Leonardo pursued "natural philosophy" at the expense of religion. However the passage was excised in the second edition, for reasons which have never been clear. And in the second edition there is the amazing statement by Vasari that at the end of his life, when he was sick and near death, Leonardo "wished to be carefully informed about the Catholic faith and about the path of goodness and the holy Christian religion".

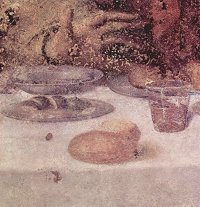

Vasari's storytelling power is evident in his passage about how the Last Supper was finished: Leonardo was having trouble imaging two of the heads - those of Judas and of Christ. The artist did not think he could find a model for one as evil as the Apostle who betrayed Christ. Since Leonardo was already notorious for his slowness in completing works of art, the prior of the church where the mural was being painted persisted with "tiresome" impatience to hassle him about completing the work. Leonardo, in front of the powerful Duke of Milan who was his great admirer, explained his difficulty in finding a model and said if he could not find anything better there was always the head of the prior who was so insistent and indiscreet. Vasari tells us that the flummoxed prior fled to his garden to harass some lowly workers and leave Leonardo in peace.

Vasari also "pretends" (in Barolsky's reading) that Leonardo encountered a similar difficulty imaging the face of Christ and therefore left it unfinished. The story shrewdly comments on the theological problem confronting any painter who would seek to probe the very mystery of the incarnation by painting the image of God incarnate. The fiction of the unfinished work relates to a deep theme of Vasari's biography, Leonardo's tendency to leave his works unfinished or "imperfect"

This aspect of the Leonardo legend, his love of perfection and his inability to finish what he attempted, became part of the legend of the artist among the Romantics of the 19th century. The aesthete Walter Pater, Oscar Wilde's teacher at Oxford, was inspired by a reading of Vasari to make his own contribution to the legend. The "painter who has fixed the outward type of Christ for succeeding centuries", writes Pater in the essay's first paragraph, "was a bold speculator, holding lightly by other men's beliefs, setting philosophy above Christianity".

This aspect of the Leonardo legend, his love of perfection and his inability to finish what he attempted, became part of the legend of the artist among the Romantics of the 19th century. The aesthete Walter Pater, Oscar Wilde's teacher at Oxford, was inspired by a reading of Vasari to make his own contribution to the legend. The "painter who has fixed the outward type of Christ for succeeding centuries", writes Pater in the essay's first paragraph, "was a bold speculator, holding lightly by other men's beliefs, setting philosophy above Christianity".

Leonardo is now seen as the representative of the ruthlessly secular aspect of the Renaissance, with almost an alchemist's or a sorcerer's faith in his magical keys to nature's innermost secrets. Leonardo's interest in humanity was intense but aloof, disdainful of conventional views, careless of politics, indifferent even to Christianity, wry to a thoroughly disquieting degree.

"Curiosity and the desire for beauty," Pater notes, "these are the two elementary forces in Leonardo's genius; curiosity often in conflict with the desire for beauty, but generating, in union with it, a type of subtle and curious grace."

Fascinated by Leonardo's smiling portraits and their mysterious aura, Pater saw them as reflections of the artist's complex inner life.

Twenty years later Oscar Wilde asked rhetorically "Who, again, cares whether Mr. Pater has put into the portrait of Mona Lisa something that Leonardo never dreamed of?"

Wilde urged readers to take a work of art simply as a starting point for their own creations, for "the meaning of any beautiful created thing is, at least, as much in the soul of him who looks at it, as it was in the soul of him who wrought it".

Here we see the origins of the very contemporary notion that the work of art belongs to the perceivers who interpret it variously according to their historical, social and psychological needs.

At the turn of the 20th century a brilliant Russian writer, Dmitri Merejkowski, wrote a novel called The Romance of Leonardo Da Vinci (1902), a profound meditation on art and religion. Merejkowski portrays Leonardo as a man of many facets, some of which may be grouped as pagan, some of which are Christian. As a result, Leonardo was filled with conflict and doubts. Striving for the unattainable, he almost never completes a work. Always dissatisfied with what he has done, the artist suffers a characteristically modern "anxiety".

Sigmund Freud may have discovered his "abnormal" Leonardo through Merejkowski's novel. The father of psychoanalysis made a notable entry into art history with an essay entitled Leonardo Da Vinci and the Memory of His Childhood (1910).

Freud pays explicit tribute to Pater's essay:

The need for a deeper reason behind the attraction of La Gioconda's smile, which so moved the artist that he was never again free from it, has been felt by more than one of his biographers. Walter Pater, who sees in the picture of Mona Lisa a 'presence... expressive of what in the ways of a thousand years men had come to desire' [1873, 118], and who writes very sensitively of 'the unfathomable smile, always with a touch of something sinister in it, which plays over all Leonardo's work' [ibid., 117], leads us into another clue when he declares (loc. cit.): 'Besides, the picture is a portrait. From childhood we see this image defining itself on the fabric of his dreams; and but for express historical testimony, we might fancy that this was but his ideal lady, embodied and beheld at last...'

By Freud's time the sense of art's futility had become a commonplace, and Freud speaks of this condition when he says that Leonardo "had some dim notion of perfection, whose likeness time and again he despairs of reproducing".

Two other books deserve to be mentioned in this sketchy survey. First, Kenneth Clark's notable monograph on the artist is by far the most balanced and penetrating short book on the subject. You should read it if you are interested in creativity, art or beauty. Second, a few years ago one of the greatest living art historians, Leo Steinberg, published Leonardo's Incessant Last Supper. On the first page he states:

Two questions arise at the mention of Leonardo's Last Supper: Is there anything left to see? and, Is there anything left to say?

In the hands of a master like Steinberg the answer to both questions is a resounding yes. One of the incontestable benefits of The Da Vinci Code will be that it will inspire readers to open up another book on this most enigmatic, restless, heterodox, and profane and as Vasari would say "divine" artist.

Artcyclopedia page for Leonardo da Vinci

Books about Leonardo on the net:

Giorgio Vasari's Life of Leonardo da Vinci

Walter Pater on Leonardo

Excerpt from Sigmund Freud's Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of his Childhood

|

Past Articles

2006

Cézanne in Provence, by Joseph Phelan

Angels in America: Fra Angelico in New York, by Joseph Phelan

2005

Notes on New York (NoNY), by Joseph Phelan

The Greatest Painting in Britain

French Drawings and Their Passionate Collectors, by Joseph Phelan

Missing the Picture: Desperate Housewives Do Art History, by Joseph Phelan

The Salvador Dalí Show, by Joseph Phelan

2004

Boston Marathon, by Joseph Phelan

Philadelphia is for Art Lovers, by Joseph Phelan

Featured on the Web: Understanding Islamic Art and its Influence, by Joseph Phelan

Independence Day: Sanford R. Gifford and the Hudson River School, by Joseph Phelan

The "Look" of Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ, by Joseph Phelan

The Importance of Being Odd: Nerdrum's Challenge to Modernism, by Paul A. Cantor

2003

Advent Calendar 2003, narrated by Joseph Phelan

If Paintings Could Talk: Paul Johnson's Art: A New History, by Joseph Phelan

Mad Max [Max Beckmann], by Joseph Phelan

Marsden Hartley: The Return of the Native, by Joseph Phelan

Jean-Antoine Houdon: Sculptor of the Enlightenment, by Joseph Phelan

Frederic Remington's Nocturnes, by Joseph Phelan

Magnificenza! Titian and Michelangelo, Manet and Velazquez, by Joseph Phelan

Masterful Leonardo and Graphic Dürer, by Joseph Phelan

Favorite Online Art Museum Features, by Joseph Phelan

Studies for Masterpieces, by John Malyon

2002

Portrait of the Artist as a Serial Killer, by Joseph Phelan

Renoir's Travelling, Bonnard's "At Home", by Joseph Phelan

The Philosopher as Hero: Raphael's The School of Athens, by Joseph Phelan

The Greatest Works of Art of Western Civilization

Celebrating Heroes; Celebrating Benjamin West, by Joseph Phelan

Chasing the Red Deer into the American Sublime (Education and the Art Museum, Part II), by Joseph Phelan

Planning Your Summer Vacation, by Joseph Phelan

Education and the Art Museum, Part I, by Joseph Phelan

Unsung Griots of American Painting, by Joseph Phelan

The British Museum COMPASS Project, interview by Joseph Phelan

Robert Hughes, Time Magazine Art Critic: Biography and Writings

2001

Software review: Le Louvre: The Virtual Visit on DVD-ROM, by Joseph Phelan

Tragedy and Triumph at Arles: Van Gogh and Gauguin, by Joseph Phelan

Her Last Bow: Sister Wendy in America, by Joseph Phelan

Love, Death and Resurrection: The Paintings of Stanley Spencer, by Joseph Phelan

Who is Rodin's Thinker?, by Joseph Phelan

Celebrations North and South, by Joseph Phelan

Rubens and his Age, by Joseph Phelan

Great Reproductions of Great Paintings

The Passion of Christ, by Joseph Phelan

Edouard Manet: Public Spaces, Private Dreams, by Joseph Phelan

Henry Moore and the British Museum: The Great Conversation, by Joseph Phelan

2000

Notorious Portraits, Part II, by John Malyon

Notorious Portraits, Part I, by John Malyon

The Other Michelangelo, by Joseph Phelan

The Art of Drawing, by Joseph Phelan

Poussin and the Heroic Landscape, by Joseph Phelan

Great Art Museums Online, by Joseph Phelan

Venetian Painting and the Rise of Landscape, by Joseph Phelan

Forbidden Visions: Mythology in Art, by Joseph Phelan

Themes in Art: The Passion of Christ, by Joseph Phelan

Web site review: Christus Rex

Web site review: National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., by Joseph Phelan

Online exhibit review: Inuit Art: The World Around Me, by John Malyon

Poll: Who is Producing the Most Interesting Art Today? (Results)

Poll: Who is Producing the Most Interesting Art Today? (Part II)

1999

Poll: Who is Producing the Most Interesting Art Today? (Part I)

Spotlight on The Louvre Museum

Spotlight on Impressionism

Spotlight on Optical Art

Spotlight on Animals in Art

Spotlight on Surrealism

Spotlight on Sculpture

Spotlight on Women in the Arts

Spotlight on The Golden Age of Illustration

Spotlight on Vincent van Gogh

Spotlight on Great Art

|