|

| |

Feature Archive

Stop, See, and Soar:

"Société Anonyme" at the expanded Phillips Collection

|

|

Two staircases, one of dark Victorian wood, the other, a circular, white conveyance built a century later, differ in design and zeitgeist, but both - from opposite ends of Washington's Phillips Collection - conduct visitors to parallel visions of modern art and something a bit rarer: dedication to the common weal.

Baronial steps of Duncan Phillips's 1897 mansion mark the first U.S. museum of modern art, opened in 1921 as the Phillips Memorial Gallery. The young art critic dedicated a specially designed room for public viewing as a means of channeling his grief upon the sudden deaths of his father in 1917 and his brother a year later. He aimed for "a beneficent force in the community."

Circular ascent in a Phillips annex leads to The Société Anonyme: Modernism for America, showcasing the life's work of a contemporaneous dynamo of art collection and education, Katherine Dreier. In 1921, when she and Société co-founders Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray incorporated their movement, she vowed to "build up a tremendous thing... to break down the prejudice which exists against the new approach to art."

Duncan Phillips (1886-1966) and Katherine Dreier (1877-1952) dedicated their lives to cultivating America's understanding and appreciation of modern art as collectors, educators, and advocates. Both also championed emerging artists. But their visions differed. Phillips, the svelte collector, saw modernism, not as breaking with the past, but as evolving from it. He thus looked for connections between modern works and their sources and favored the School of Paris.

Artist Dreier, whose matronly appearance and frilly dresses cloaked a dedicated revolutionary, sought to form a global network of living artists and showcase such radical departures from the past as German Expressionism, Russian Constructivism, and Dada.

Fittingly, as the Phillips Collection celebrates another expansion and launches its Center for the Study of Modern Art, Société Anonyme [S. A.] hangs as a "labor of love," according to senior curator Elizabeth Hutton Turner. "We waited for this moment: for new galleries to be ready." The exhibit spans four decades of the 20th century in its 150 works by over 50 artists. S.A.'s dictum: stay "ahead or abreast of the times... to stimulate the imagination and inventive attitude in America."

Toward that end, S.A. generated thirty publications, more than eighty contemporary art exhibitions, and 85 public programs. It also sponsored the first one-artist shows in the U.S. by Kandinsky (1923), Klee (1924) and Léger (1925) and helped European artists flee the guns of '39. By the time it closed down on its 30th anniversary in 1950, S.A.'s cache included more than 1000 works of art.

Largely unrecognized, Dreier doesn't come easily to mind as a name yoked to that of conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp (1886-1968), but her 1916 introduction to the Frenchman spawned what would become her life's work: cultivating U.S. appreciation of modern art. Their alliance would last till Dreier's 1952 death and alter, not only modern art, but concepts of museology, such as S.A.'s "museum without walls."

When the two met, Dreier, at 39, was the daughter of wealthy German immigrants who had raised her to be free-thinking and socially minded. Art classes led to Whistlerian canvases until, following travels across Europe, she began to emulate the style of Kandinsky, whom she deemed a kindred soul for believing in art's spiritual value versus the materialism of an industrialized world.

Duchamp, 30, a recently arrived French boulevardier, whose Fountain (aka urinal) would ensure notoriety, enjoyed an international network and social grace that complemented Dreier's deft administrative talents.

The Société's April 30, 1920 inaugural is recreated in the first room, with ten works framed by Duchamp's Dadaist irreverence: lace doilies. Two standouts immediately captivate the viewer: Man Ray's zestful color pentagon, Revolving Doors (1926) and Joseph Stella's majestic, chromatically intense and futuristic Brooklyn Bridge (1918-20). Stella's watercolor/gouache Study for New York Interpreted - by itself a little gem - hangs around the corner. Nearby come four Klees, with the Herald of Autumn, a 1922 watercolor, alone worth the trip for its mesmerizing "gradation study," in green, violet and orange.

The second room's six canvases explode with color from S.A.'s two most-exhibited artists. Kandinsky scintillates with Multicolored Circle (1921) and Heinrich Campendonk - influenced by religious mysticism and German folk art - pours out blood-red cubism and absinthe-toned flesh.

Next comes a representation of Dreier's most lasting legacy: the "International Exhibition of Modern Art," which opened at the Brooklyn Museum in November, 1926. From Miró to Mondrian, many artists made their U.S. debuts in this headliner of more than 300 works by 106 artists from 19 countries. The show's success branded S.A. nonpareil in the study and promotion of modern art and fascinated young artists like Mark Rothko and Stuart Davis. Dreier maintained the momentum with heavy schedules of educational films, lectures and courses - even concerts and dance recitals.

Here are Blaue Reiter alum Franz Marc's 1913 Deer in the Forest and Francis Picabia's Midi (Promenade des Anlgais) (ca. 1923), a mixture of oil, feathers, macaroni and leather framed in snakeskin. A facsimile of Dreier's 1926 Art Deco catalogue heralds "Fellow Fighters in the Field of Battle for Greater Modern Art... bigger than any one nationality."

Gallery-goers facing creative blocks might draw inspiration from Stefi Kiesler's Typo-Plastics. Beginning in 1925, she typed her way through 100 images using just red and black ink, as with the march of percentage signs to a squad of W's, red M's standing attention on the left.

Final highlights include three unvarnished Mondrians, Kurt Schwitters's Radiating World (1920), with "mouvement Dada" collaged among blue and green angles, Kasimir Malevich's The Knife Grinder (1912-13), and Calder's Fourth Flurry, (1948) whose rare white disks limn gently falling snow.

Why are Dreier and the S.A. so little known? Yale exhibit curator Jennifer Gross posits the following: first, Dreier ran activities out of Connecticut, with Duchamp often on the Paris end, both distant from the New York art community. The two were idiosyncratic, private individuals, sometimes not sharing information - even with each other. Dreier's sense of mission, Gross's richly illustrated catalogue notes, could make her "explosively opinionated." Also, her emphasis on German and Russian art - in some quarters ill-timed - collided with the popularity of French works.

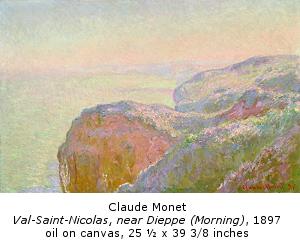

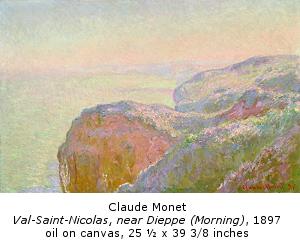

French masters indeed intrigued Duncan Phillips. In 1923, to secure renown for his young museum, he purchased Pierre-Auguste Renoir's Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880-81) - "the only Renoir I need." On view surrounding the riverside repast is Phillips's practice of arranging paintings to "bring together congenial spirits," encouraging "conversations" among the works. To the right of Renoir, savor Claude Monet's delicate: Val-Saint-Nicolas, near Dieppe (Morning) (1897). A Bonnard, a late, beautifully geometric Cézanne, and a Sisley snowscape complete the "chatting" canvases.

French masters indeed intrigued Duncan Phillips. In 1923, to secure renown for his young museum, he purchased Pierre-Auguste Renoir's Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880-81) - "the only Renoir I need." On view surrounding the riverside repast is Phillips's practice of arranging paintings to "bring together congenial spirits," encouraging "conversations" among the works. To the right of Renoir, savor Claude Monet's delicate: Val-Saint-Nicolas, near Dieppe (Morning) (1897). A Bonnard, a late, beautifully geometric Cézanne, and a Sisley snowscape complete the "chatting" canvases.

By 1930, Phillips's growing collection - currently over 2,400 works, half American - nudged the family to new quarters. He converted the entire Greek Revival mansion into the Phillips Collection, in which he sought to create, "instead of the academic grandeur of marble halls and... miles of chairless spaces, ... an intimate, attractive atmosphere - as we associate with a beautiful home."

Intimacy - up, down steps, always steps, integral to the manse's charm - is the international byword of this Dupont Circle landmark. In what welcomes the visitor like one's second, albeit grander, living room, the museum-goer can sit and study a Degas bather or a brace of Puvis de Chavannes paintings. Ascending the baronial wood staircase leading from the original carriage entrance past a still-functioning 1910 grandfather clock, one might perch on a window seat, wishfully refracting Arthur Dove's blazing Red Sun (1935) rays onto winter greyness outside. Past tiled fireplaces, stop to reflect on John Henry Twachtman's subtle whites in Winter (undated).

Many additional canvases found exhibit space this year as the Phillips gained 30,000 square feet. Named for the chief donors, the Sant Wing adds two-story galleries particularly suited to post-1950s art, such as John Walker's Untitled (1976), a huge canvas/collage of cobalt and yellow poised to inject vitality into even the most weary gallery-goer.

By constructing 65 per cent of the museum's expansion below ground, the renovation preserves the museum's intimate atmosphere. Lower levels afford new educational spaces, an expanded library and archives, and a 180-seat auditorium. Outside a most welcome courtyard has bloomed, with benches, birdsong and bronzes by Ellsworth Kelly and Barbara Hepworth.

Reinstalled, but not changed, is the famed Rothko Room, ablaze with green, tangerine, and red in four 1953-57 canvases, in dimensions agreed upon by both artist and collector when the space was specially constructed in 1960.

In the carriage house behind the museum, the Phillips this autumn launched classes in its Center for the Study of Modern Art, in partnership with the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Professor Jonathan Fineberg directs the program. [Course descriptions may be found at: http://www.phillipscollection.org/html/center.html. To register for spring classes, open until Jan. 29, 2007, consult: http://www.art.uiuc.edu/projects/phillips/.]

Although Washington Post architecture critic Benajmin Forgey lambasted the city-mandated preservation of an historical apartment building fašade behind which the expansion took shape as "hiding behind a frumpy relic," the added resources, particularly the state-of-the-art auditorium and the carriage house's classrooms, resoundingly deliver Duncan Phillips's dream into the 21st century.

Perhaps in the Phillips mold, Dreier had hoped to turn her Connecticut home - rich with works by Brancusi and Duchamp, including the latter's 10-foot long, scroll-like Tu'm, (1918) - into a "country museum," based on her thought that visitors seeing radically new art in a domestic setting wouldn't shock easily. By 1941, when hope was extinguished, she arranged to give Yale the S.A. collection.

In the end, these two philanthropic collectors' pathways met, just as Duchampian black ovals on the glass skywalk guide the visitor back into Duncan Phillips's childhood home. Phillips donated paintings to S.A. In turn, when Duchamp, as Dreier's executor, offered Phillips 41 potential gifts from her private collection, he chose 17, including one of the Collection's best-loved works: Klee's Little Regatta (1922).

Their credos dovetailed: stop, see, and soar! Phillips declared art "a joy-giving, life-enhancing influence, assisting people to see beautifully, as true artists see." Dreier pronounced "the function of art... to free the spirit of man and invigorate and enlarge his vision."

Exhibition website (Yale University Art Gallery)

|

|

Just as the organization's signboard, Société Anonyme, Inc., is of unknown origin, the group's name isn't fully explained in Société annals. Dreier initially chose Modern Ark, until Man Ray came up with Société Anonyme, Inc., on the notion that anonymous society in French would be appropriate for a project organized by artists for artists.

When Duchamp explained that the appellation didn't directly translate into English, but meaninglessly signified "Incorporated, Inc.", the trio liked its Dadaist twist even better.

The show runs through January 21, 2007 at the Phillips, then travels to the Dallas Museum of Art (June 10 - Sept. 16, 2007), Nashville's Frist Center for the Visual Arts (Oct. 26, 2007- Feb. 3, 2008), and finally home to the Yale University Art Gallery in autumn, 2010.

|

|

Past Articles

2006

Constable's Great Landscapes, by Joseph Phelan

Editorial: Save Studio 60 (from needing to be saved), by John Malyon

Far From Heaven: Anselm Kiefer at the Hirshorn, by Joseph Phelan

Henri Rousseau: Self-Taught in Paris, by K. Kimberly King

Klee, Hitler and America, by Joseph Phelan

Anyone For Venice?, by Joseph Phelan

The Legends of Leonardo, by Joseph Phelan

Hey, "Dada"-Dude, Where's the Rest of Me?, by K. Kimberly King

Cézanne in Provence, by Joseph Phelan

Angels in America: Fra Angelico in New York, by Joseph Phelan

2005

Notes on New York (NoNY), by Joseph Phelan

The Greatest Painting in Britain

French Drawings and Their Passionate Collectors, by Joseph Phelan

Missing the Picture: Desperate Housewives Do Art History, by Joseph Phelan

The Salvador Dalí Show, by Joseph Phelan

2004

Boston Marathon, by Joseph Phelan

Philadelphia is for Art Lovers, by Joseph Phelan

Featured on the Web: Understanding Islamic Art and its Influence, by Joseph Phelan

Independence Day: Sanford R. Gifford and the Hudson River School, by Joseph Phelan

The "Look" of Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ, by Joseph Phelan

The Importance of Being Odd: Nerdrum's Challenge to Modernism, by Paul A. Cantor

2003

Advent Calendar 2003, narrated by Joseph Phelan

If Paintings Could Talk: Paul Johnson's Art: A New History, by Joseph Phelan

Mad Max [Max Beckmann], by Joseph Phelan

Marsden Hartley: The Return of the Native, by Joseph Phelan

Jean-Antoine Houdon: Sculptor of the Enlightenment, by Joseph Phelan

Frederic Remington's Nocturnes, by Joseph Phelan

Magnificenza! Titian and Michelangelo, Manet and Velazquez, by Joseph Phelan

Masterful Leonardo and Graphic Dürer, by Joseph Phelan

Favorite Online Art Museum Features, by Joseph Phelan

Studies for Masterpieces, by John Malyon

2002

Portrait of the Artist as a Serial Killer, by Joseph Phelan

Renoir's Travelling, Bonnard's "At Home, by Joseph Phelan

The Philosopher as Hero: Raphael's The School of Athens, by Joseph Phelan

The Greatest Works of Art of Western Civilization

Celebrating Heroes; Celebrating Benjamin West, by Joseph Phelan

Chasing the Red Deer into the American Sublime (Education and the Art Museum, Part II), by Joseph Phelan

Planning Your Summer Vacation, by Joseph Phelan

Education and the Art Museum, Part I, by Joseph Phelan

Unsung Griots of American Painting, by Joseph Phelan

The British Museum COMPASS Project, interview by Joseph Phelan

Robert Hughes, Time Magazine Art Critic: Biography and Writings

2001

Software review: Le Louvre: The Virtual Visit on DVD-ROM, by Joseph Phelan

Tragedy and Triumph at Arles: Van Gogh and Gauguin, by Joseph Phelan

Her Last Bow: Sister Wendy in America, by Joseph Phelan

Love, Death and Resurrection: The Paintings of Stanley Spencer, by Joseph Phelan

Who is Rodin's Thinker?, by Joseph Phelan

Celebrations North and South, by Joseph Phelan

Rubens and his Age, by Joseph Phelan

Great Reproductions of Great Paintings

The Passion of Christ, by Joseph Phelan

Edouard Manet: Public Spaces, Private Dreams, by Joseph Phelan

Henry Moore and the British Museum: The Great Conversation, by Joseph Phelan

2000

Notorious Portraits, Part II, by John Malyon

Notorious Portraits, Part I, by John Malyon

The Other Michelangelo, by Joseph Phelan

The Art of Drawing, by Joseph Phelan

Poussin and the Heroic Landscape, by Joseph Phelan

Great Art Museums Online, by Joseph Phelan

Venetian Painting and the Rise of Landscape, by Joseph Phelan

Forbidden Visions: Mythology in Art, by Joseph Phelan

Themes in Art: The Passion of Christ, by Joseph Phelan

Web site review: Christus Rex

Web site review: National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., by Joseph Phelan

Online exhibit review: Inuit Art: The World Around Me, by John Malyon

Poll: Who is Producing the Most Interesting Art Today? (Results)

Poll: Who is Producing the Most Interesting Art Today? (Part II)

1999

Poll: Who is Producing the Most Interesting Art Today? (Part I)

Spotlight on The Louvre Museum

Spotlight on Impressionism

Spotlight on Optical Art

Spotlight on Animals in Art

Spotlight on Surrealism

Spotlight on Sculpture

Spotlight on Women in the Arts

Spotlight on The Golden Age of Illustration

Spotlight on Vincent van Gogh

Spotlight on Great Art

|

French masters indeed intrigued Duncan Phillips. In 1923, to secure renown for his young museum, he purchased Pierre-Auguste Renoir's Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880-81) - "the only Renoir I need." On view surrounding the riverside repast is Phillips's practice of arranging paintings to "bring together congenial spirits," encouraging "conversations" among the works. To the right of Renoir, savor Claude Monet's delicate: Val-Saint-Nicolas, near Dieppe (Morning) (1897). A Bonnard, a late, beautifully geometric Cézanne, and a Sisley snowscape complete the "chatting" canvases.

French masters indeed intrigued Duncan Phillips. In 1923, to secure renown for his young museum, he purchased Pierre-Auguste Renoir's Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880-81) - "the only Renoir I need." On view surrounding the riverside repast is Phillips's practice of arranging paintings to "bring together congenial spirits," encouraging "conversations" among the works. To the right of Renoir, savor Claude Monet's delicate: Val-Saint-Nicolas, near Dieppe (Morning) (1897). A Bonnard, a late, beautifully geometric Cézanne, and a Sisley snowscape complete the "chatting" canvases.