Feature Archive |

August, 2001

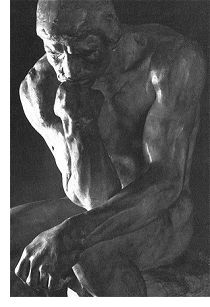

Who is Rodin's Thinker?

| By Joseph Phelan |

One of the finest collections of Auguste Rodin's work - models and bronzes - will go on display at the Royal Ontario Museum on Sept. 20. This is good news for art lovers, especially in Canada. After touring the world, the collection will be installed in a new museum in the Ontario town of Barrie. The museum will be the centerpiece of a proposed "Art City" devoted to housing fine art exhibits on tour.

One of the finest collections of Auguste Rodin's work - models and bronzes - will go on display at the Royal Ontario Museum on Sept. 20. This is good news for art lovers, especially in Canada. After touring the world, the collection will be installed in a new museum in the Ontario town of Barrie. The museum will be the centerpiece of a proposed "Art City" devoted to housing fine art exhibits on tour.Rodin's gorgeous bronze and marble sculptures - erotically charged or tormented and defeated - are surely the perfect choice for such a venture. Rodin is the Wagner of modern sculpture; he is one of those rare artists whose work speaks to the deep longings in most people, yet one whose work repays repeated visits and study. Discriminating viewers will be struck by the haunting depth of vision and the artist's impeccable craftsmanship.

Rodin is also one of those artists who form a bridge between the Romanticism of the 19th century and the Modernism of the 20th, allowing us to see how we arrived at where we are now. A good example is his first bust, The Man With the Broken Nose (1864), inspired by an old workman with a smashed in nose who yet had some of the features of a Greek bust. For the first time a sculptor took as his model not the perfection of classical sculpture but its present day fragmentary condition. Almost all busts that survive from antiquity have broken noses, just as most antique statues have lost heads, hands and other extremities. Rainer Maria Rilke, who was Rodin's secretary for a time, may have been inspired by his fragments to write one of his greatest poems - The Archaic Torso.

Unfortunately there is a side of Rodin's work that has become kitsch through cheap reproductions and commercial rip-offs. This includes some of his best pieces like The Three Shades, and especially The Thinker.

Cultural kitsch has a way of containing long lost loveliness, if you know how to rub off the patina hiding the bronze. I asked a group of savvy art students and cognoscenti who The Thinker was. A few graduate students thought it could be a famous philosopher, perhaps Plato, or even Nietzsche's Superman; I reminded them that Nietzsche was unknown to the world when Rodin created The Thinker, and Plato wasn't even close. A few said it reminded them of the young Marlon Brando with his perfect body from his Streetcar Named Desire days.

One wit said it was the young Brando in one of his heavy sessions at the Actors Studio, all naked and angst ridden, doing a philosopher manqué: "I could have been a think -er."

Rodin's Story

Auguste Rodin (b. 1840, Paris) was a poor boy with a rich talent for drawing who trained at the École Spéciale de Dessin et de Mathématique, a school with a mission to educate the designers and the artisans of the French nation. He was rejected three times by the École des Beaux Arts, the official art school of France. Rejection proved to be fortunate for this young artist because it forced him to find work among the commercial decorators and ornamental craftsmen of Paris. He was especially lucky to find employment in the studio of Carrier-Belleuse. Carrier-Belleuse had a sharp sense of how to combine historical themes with new technologies and the process of mass production. During and after the Franco-Prussian War, Carrier-Belleuse took his young apprentice to Brussels to help build public monuments commissioned by the Belgian Government.

A trip to Italy in 1875 further opened Rodin's eyes to the achievement of the past: Michelangelo, Donatello and Ghilberti. "Michelangelo saved me from academicism," he later noted. Michelangelo's magnificent young male aristocrats, muscular ignudi, grave prophets, enigmatic sibyls, heroic biblical figures, and his tormented, terrified and hell-bound sinners were to haunt Rodin's imagination for the rest of his life. In turn, Rodin's imagination revived the nearly dead art of sculpture in the late 19th century and provided inspiration for artists of the 20th century.

Rodin's vision of man in his misery and greatness found its center when he received a commission from the French Government to create a portal for the entrance to the Museum of Decorative Art. The theme of the portal was Dante's Divine Comedy. Whether or not Rodin had read Dante before this commission is unimportant: the brooding presence of this other great Florentine inspired and overwhelmed him, as he sat down to read and prepare hundreds of sketches for the work.

The 19th century rediscovered Dante's poetry as well as many other things about the Middle Ages. For the first time since the Renaissance, Europe was receptive to the works and the spirit of its Christian past. Compared to the failures of the Age of Reason, especially post-Napoleonic Europe, the Middle Ages seemed like an era of spiritual health and artistic greatness. The Divine Comedy, considered to be the greatest marriage of European poetry and philosophy, and rivaled only by the pagan epics of Homer and Virgil, became a bestseller. Auguste Rodin had a passion for the Inferno; Dante's journey through hell was his inspiration, visualizing the characters became his career.

Then on a trip to London in 1882 Rodin discovered his British contemporaries, the so-called Pre-Raphaelite painters.

These Painters had already turned to illustrating Dante. In this they were influenced by William Blake (1757-1827), poet and visual artist extraordinary who had created a remarkable series of illustrations for "the greatest poem ever written".

Rodin studied Blake's illustrations of Dante on his return to Paris, thus enlarging his vision and ambitions. (We cannot overlook the influence of the first great illustrator of the Divine Comedy, Botticelli, who was the favorite of the Pre-Raphaelites as well as a strong influence on Blake's linear style.)

The combination of Dante's epic, Blake's drawings and the gigantic example of Michelangelo proved to be a potent cocktail, fueling Rodin for the next 40 years. Furthermore, it pushed him in the opposite direction from the painters of his period - the Salon favorites and the Impressionists and the Post-Impressionists.

Thus the project expanded. Rodin took to calling the portal project The Gates of Hell. By using this title, he linked his doors with a famous work of the Renaissance: Ghilberti's Doors for the Florence Baptistery, which illustrate scenes from the Old Testament. These doors, which Michelangelo carefully studied, are known as the Gates of Paradise. But the twisted and anguished figures come from Michelangelo's Last Judgment.

Rodin never completed the huge work The Gates of Hell in a definitive form (he worked on it intermittently until 1900 and the museum never came into being in its proposed form), but he poured some of his finest creative energy into it. Even unfinished and unfinishable it served as a kind of matrix from which Rodin could draw as many as 200 individual pieces including such well-known works as The Kiss and The Thinker.

The Thinker was originally meant to be Dante in front of the Gates of Hell, pondering his great poem. Dante as a voluptuous naked male may seem absurd to those who think of the images painted in his time and after, but Dante's head does bear some resemblance to the profile of The Thinker. Moreover, Dante's headdress is distinctive and seems to be indicated by the markings Rodin made on his working copy of The Thinker.

Why is The Thinker naked? Because Rodin wanted a heroic figure à la Michelangelo to represent Thinking as well as Poetry.

Rodin's Answer

Rodin himself wrote about his intention:

The Thinker has a story. In the days long gone by I conceived the idea of the Gates of Hell. Before the door, seated on the rock, Dante thinking of the plan of the poem behind him... all the characters from the Divine Comedy. This project was not realized. Thin ascetic Dante in his straight robe separated from all the rest would have been without meaning. Guided by my first inspiration I conceived another thinker, a naked man, seated on a rock, his fist against his teeth, he dreams. The fertile thought slowly elaborates itself within his brain. He is no longer a dreamer, he is a creator.The work of Rodin resonates with the great aspirations of the 19th century, the century of Darwin, Marx and Wagner. But in his equation, The Thinker = the Poet = the Creator, Rodin was way ahead of his time. The greatest German Philosopher of the 20th century, Martin Heidegger, only began to formulate this equation in the 1930's in such works as "The Thinker as Poet", "What are Poets For?" and "...Man Dwells Poetically". Now it is a commonplace of humanities departments, repeated endlessly by such luminaries as Derrida, Lyotard, Richard Rorty and their followers.

Discover dozens of works by this artist on the Artcyclopedia page for Auguste Rodin.

This article is copyright 2001 by Joseph Phelan. Please do not republish any portion of this article without written permission.

Joseph Phelan can be contacted at joe.phelan@verizon.net

Past Articles

July, 2001

Celebrations North and South, by Joseph Phelan

June, 2001

Rubens and his Age, by Joseph Phelan

May, 2001

Great Reproductions of Great Paintings

April, 2001

The Passion of Christ, by Joseph Phelan

March, 2001

Edouard Manet: Public Spaces, Private Dreams, by Joseph Phelan

February, 2001

Henry Moore and the British Museum: The Great Conversation, by Joseph Phelan

December, 2000

Advent Calendar 2000, narrated by Joseph Phelan

November, 2000

Article: Notorious Portraits, Part II, by John Malyon

October, 2000

Article: Notorious Portraits, Part I, by John Malyon

Article: The Other Michelangelo, by Joseph Phelan

September, 2000

Article: The Art of Drawing, by Joseph Phelan

August, 2000

Article: Poussin and the Heroic Landscape, by Joseph Phelan

July, 2000

Article: Great Art Museums Online, by Joseph Phelan

June, 2000

Article: Venetian Painting and the Rise of Landscape, by Joseph Phelan

May, 2000

Article: Forbidden Visions: Mythology in Art, by Joseph Phelan

April, 2000

Article: Themes in Art: The Passion of Christ, by Joseph Phelan

Web site review: Christus Rex

March, 2000

Web site review: National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., by Joseph Phelan

Online exhibit review: Inuit Art: The World Around Me, by John Malyon

February, 2000/Poll: Who is Producing the Most Interesting Art Today? (Results)

January, 2000/Poll: Who is Producing the Most Interesting Art Today? (Part II)

December, 1999/Poll: Who is Producing the Most Interesting Art Today? (Part I)

November, 1999/The Louvre Museum

Web site review: The Louvre

October, 1999/Impressionism

Web site review: North Carolina Museum of Art

September, 1999/Optical Art

Web site review: The Butler Institute of American Art

August, 1999/Animals in Art

Web site review: National Museum of Wildlife Art

Online exhibit review: PBS: American Visions

July, 1999/Surrealism

June, 1999/Sculpture

Web site review: Carol Gerten's Fine Art

Online exhibit review: Michael Lucero: Sculpture 1976-1995

May, 1999/Women in the Arts

Web site review: National Museum of Women in the Arts

Online exhibit review: Jenny Holzer: Please Change Beliefs

April, 1999/The Golden Age of Illustration

Web site review: Fine Arts Museums Of San Francisco

Online exhibit review: Treasure Island and Robinson Crusoe online

March, 1999/Vincent van Gogh

Web site review: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Web site review: The Vincent van Gogh Information Gallery

February, 1999/Great Art

Web site review: The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Online exhibit review: John Singleton Copley: Watson and the Shark